“How can we expect anyone to question their deeply held beliefs if we won’t do so ourselves?”

We looked at how 39 U.S.-based bridging and contact programs describe themselves. Here’s what we found.

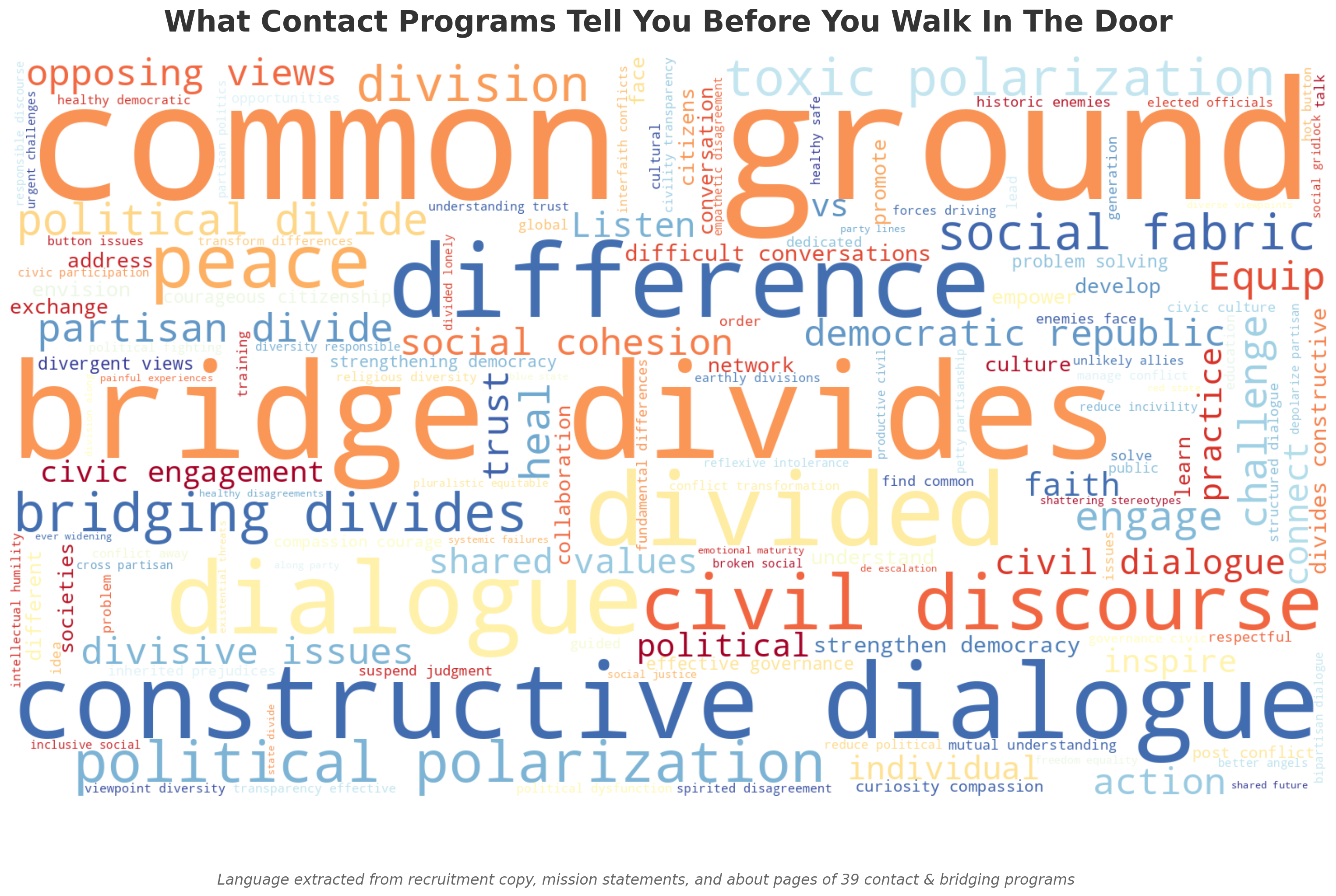

Look at this image.

Public-facing language from 39 contact and bridging programs. Sources include Listen First Coalition members, Bridge Alliance partners, and programs listed in the Columbia and Princeton bridging directories.

This is a word cloud built from the public-facing language of 39 contact and bridging programs — Braver Angels, Seeds of Peace, Interfaith America, and 36 others. Not their internal curricula. Not their facilitator guides. Just the language these organizations chose to put on their websites — mission statements, about pages, and program descriptions.

This is the language that shapes everything downstream: how a program gets covered, how it gets funded, and how a friend describes it when they invite you to come.

Now look at some of the biggest.

Toxic polarization. Political polarization. Division. Divided. Divides. Partisan divide. Opposing views. These are the diagnoses — what the programs say is wrong with you or the world.

Common ground. Bridge divides. Constructive dialogue. Dialogue. Civil discourse. Heal. Peace. These are the prescriptions — what the programs promise to do about it.

Democratic republic. Social fabric. Social cohesion. Civic engagement. Strengthen democracy. Shared values. These are the institutional values — the worldview the programs assume you share.

Every single dominant word is doing one of three things: telling you what’s broken, telling you how the program will fix it, or telling you what you should believe. Not one of the biggest words describes something a participant does. Not one describes curiosity, or surprise, or the simple experience of meeting someone new. The language is entirely about the institution’s goals, not the person’s experience.

Compare this with how other organizations talk to the people they’re trying to reach. We ran the same word cloud exercise on Amazon, Nike, and the U.S. Military. The biggest word in Amazon’s public-facing language? Customer. Nike’s? Athlete. The U.S. Military’s? Yourself. In every case, the dominant word is the person they’re trying to reach — who they are or what they get.

Now look at the bridging field’s biggest word: common ground. It’s an institutional concept. Not a person. Not an experience. A prescription.

The military comparison is especially worth thinking about. The U.S. Armed Forces recruit 18-year-olds from every background in America — and they figured out decades ago that you don’t lead with “the geopolitical threat landscape requires institutional resilience.” You lead with adventure, skills, purpose, and benefits. You lead with what the recruit gets, not what the institution needs.

A few years ago, we suggested at a conference that bridging programs should offer opportunities, not interventions. We got mostly blank stares.

That’s not an accident. And it has consequences.

Who Finds This Language Appealing?

Think about the kind of person who reads “bridge the partisan divide through constructive dialogue” and feels invited. That person probably identifies as moderate or independent. They probably experience political conflict as stressful rather than necessary. They’re comfortable with structured conversation and therapeutic-style framing. They trust that an NGO or university has the authority to diagnose social problems and offer solutions. They’re likely college-educated. They use words like “polarization” themselves.

This is not the general population. This is a specific slice of it.

Who Finds This Language Alienating?

Now think about the person who reads the same sentence and moves on. They’re not necessarily closed-minded or hostile to conversation. They might simply hold strong convictions and not see their own positions as “polarized” — they see them as correct. They might hear “toxic polarization” and feel accused rather than invited. They might hear “civil discourse” and think of a particular social class telling them to be quieter. They might hear “dialogue” and picture a room where a facilitator tells them how to feel.

Or they might simply not trust the kind of organization that talks this way.

That last one matters more than anything else in this analysis, because it’s not a personality type. It’s a growing majority.

This Is Institutional Language

Read the biggest words in the cloud one more time. “Common ground.” “Bridge divides.” “Constructive dialogue.” “Civil discourse.” “Social fabric.” “Political polarization.” “Strengthen democracy.”

These are not how most people talk — not at the dinner table, not at the bar, not at church, not on the job site. They are the vocabulary of universities, foundations, NGOs, and policy institutes. They are institutional language — and they mark every program that uses them as an institutional product.

That used to matter less than it does now.

According to the 2026 Edelman Trust Barometer — the most comprehensive global measure of institutional trust, surveying 34,000 people across 28 countries — for the first time in the survey’s 26-year history, business is now rated more ethical than NGOs. That’s a meaningful shift for a field where virtually every bridging program carries an NGO brand.

The broader picture is worse. Across Edelman’s 26-market average, 57 percent of respondents report moderate or high “grievance” — the belief that institutions serve narrow interests and make ordinary people’s lives harder. Among those with high grievance, trust drops sharply across all four institution types Edelman measures: government, business, media, and NGOs.

Seventy percent of respondents say they are unwilling or hesitant to trust someone with different values, approaches to social issues, backgrounds, or information sources. The mass-class trust gap — the difference in institutional trust between high-income and low-income populations — has more than doubled since 2012, reaching 29 points in the United States, the widest of any country measured.

And here’s the finding that should keep the bridging field up at night: trust is migrating away from institutions and toward proximate relationships. Neighbors, family, friends, and local leaders are all gaining trust. National organizations, NGOs, and media are losing it. People increasingly trust what’s close to them and distrust what’s far away.

Now look at the word cloud one more time. Every dominant word is NGO vocabulary. Every program behind those words is an institutional product, built by the kinds of organizations that a growing majority of people no longer trust to act in their interest.

The Recruitment Language Is The Recruitment Filter

The bridging field’s most persistent problem is self-selection: these programs mostly reach people who already agree with their premise. The standard explanation is that resistant populations are hard to recruit. The standard response is to try harder — better marketing, more targeted outreach, partnerships with trusted community leaders.

But what if the problem is simpler than that? What if the recruitment language itself is the filter?

To find a typical bridging program’s recruitment appealing, a person has to clear three hurdles at once. They have to accept the diagnosis — agree that polarization, division, or prejudice is the problem worth focusing on, rather than economic inequality, institutional failure, or legitimate political disagreement. They have to accept the prescription — be willing to enter a structured process designed to change their attitudes and build empathy, and trust that the facilitators are neutral. And they have to trust the institution — believe that the NGO or university running the program has the authority to diagnose what’s wrong and tell them how to fix it.

The population that clears all three hurdles is remarkably specific: educated, institutionally trusting, conflict-averse, moderate-identifying, and already sympathetic to the program’s values. These are people who would describe themselves as “exhausted by polarization.” They are, by definition, the choir.

Everyone else — the strongly convicted, the institutionally distrustful, the people who think the real problem is something other than polarization, the people who hear “dialogue” and think “that’s not going to pay my rent” — never encounters the program. Not because they were turned away, but because the recruitment language told them, in 50 words or less, that this program was not for them.

What If You Started With The Participant’s Experience?

We’re writing this because we’ve been wrestling with the same question. At Acquaint, stripping prescriptive language from our platform has been a constant, deliberate effort — and one we still haven’t finished. We catch ourselves reaching for words like “bridge” and “divide” all the time. It’s the water the field swims in.

Right now, our recruitment says: “Practice human connection.” Three words. No diagnosis. No prescription. No institutional signal. We’re proud of that language, but we know we have a long way to go — in our copy, in our framing, in how we talk about what we do. This analysis held a mirror up to us, too.

What we’ve found so far is that when you describe an activity rather than an intervention, different things happen. People show up for every reason imaginable. They’re curious. They’re bored. They want to practice English. They’re lonely. They saw a friend do it. None of these motivations require accepting a diagnosis about what’s wrong with the world. And yet the outcomes volunteers describe — expanded perspectives, corrected stereotypes, a feeling that the world got bigger — are the same outcomes every bridging program is working toward.

We believe genuine human connection is a prerequisite for better understanding and collaboration — not something you prescribe as the outcome. You create the conditions for it. Then you get out of the way. But we’re still learning what that looks like in practice, and we love to learn alongside the organizations doing this work.

The Question For The Field

This is not a criticism of any individual program. The organizations in this analysis do important, careful work. The question is about the field’s shared language — the vocabulary that has become so standard that nobody notices it anymore.

When 39 programs spanning seven categories of contact work, run by different organizations with different methods in different contexts, all converge on the same cluster of words — common ground, bridge divides, constructive dialogue, civil discourse, toxic polarization — that’s not a coincidence. It’s a culture. And cultures have blind spots.

The blind spot here is that this language feels neutral to the people who use it. If you work in this field, these words are just how you describe what you do. But to someone outside the field — someone who didn’t go to the same conferences, read the same papers, share the same institutional commitments — these words are not neutral. They’re a signal. And increasingly, the signal they send is: this is not for you.

There is an irony worth naming here. Many of these programs exist, explicitly or implicitly, to rebuild trust — trust between groups, trust in democratic institutions, trust in the possibility of cooperation. But by packaging that goal in institutional language, delivered through institutional channels, they replicate the very dynamic they’re trying to fix. You cannot rebuild trust by deploying the vocabulary of the institutions people no longer trust. The medium undermines the message.

The bridging field’s recruitment problem is not a marketing problem. It is a language problem that reveals a design problem. These programs cannot recruit beyond the choir because the recruitment language is the choir test.

Imagine a different word cloud. One where the biggest words were: curiosity. Fun. Laughter. Be heard. Meet new people. Challenge yourself. Learning. Purpose. Help others. What if the language described what a participant might actually experience, rather than what the institution hopes to achieve? What if it sounded less like a grant proposal and more like an invitation?

There’s an old line: if you love something, set it free. The bridging field may need its own version. The outcomes this work cares about most — empathy, openness, the discovery that someone different from you is also fully human — are things that emerge from genuine encounter. They cannot be prescribed into existence. And the harder you grip the outcome, the less room you leave for the encounter itself.

Maybe the field doesn’t need better outreach. Maybe it needs to let go of the outcome — and trust that what people find on the other side of a real conversation might not look like what we planned. It might look better.

• • •

Note On Methodology

This analysis examines shared language patterns across the U.S. bridging field, not the quality or impact of any individual program. We extracted verbatim text — mission statements, about pages, and program descriptions — from the public-facing websites of 39 contact and bridging programs. The word cloud was generated from the combined text of all 39 organizations. While this analysis is U.S.-focused, we hope it serves as a useful comparison for practitioners and researchers working in other contexts. Full methodology, raw data, and individual source records are available at this Google Drive folder.

Organizations included: AllSides, American Exchange Project, Better Arguments Project, Bridge Alliance, BridgeUSA, Braver Angels, Citizen Connect, Civics Unplugged, Common Ground Committee, Convergence Center for Policy Resolution, Crossing Party Lines, Difficult Conversations Project, Divided We Fall, Essential Partners, Everyday Democracy, Greater Good Science Center (Bridging Differences), Hands Across the Hills, Hi From The Other Side, Interfaith America, Listen First Project, Living Room Conversations, Mediators Beyond Borders International, More in Common, NCDD, Neighborly Faith, National Institute for Civil Discourse, One America Movement, PeacePlayers International, Resetting the Table, Search for Common Ground, Seeds of Peace, Sisterhood of Salaam Shalom, Soliya, Starts With Us / Builders Movement, Sustained Dialogue Institute, Unify America, Urban Rural Action, Village Square, and Weave (Aspen Institute).

Institutional trust data: 2025 and 2026 Edelman Trust Barometer (edelman.com/trust).

Alex is Co-founder and CTO of Acquaint. Acquaint is a nonprofit building infrastructure for human connection, facilitating one-on-one conversations between volunteers in 110+ countries through its Global Conversations program. Learn more at acquaint.org.